How Light Affects Hormones + Best Melatonin Dose for Women

Lunaception, Light and the Mind-Body Question

In my doctoral capstone I explored the idea that menstrual cycles, sleep, and hormones might be more deeply entangled with light and lunar rhythms than modern life allows us to notice.

One book that kept finding its way back into my hands was “Lunaception” by Louise Lacey—a 1970s text describing how women might sync their cycles to the moon by sleeping in near-total darkness most of the month, and then introducing a few nights of light (traditionally around the Full Moon). The premise wasn’t just fertility; it was reclaiming the body’s relationship to natural light and dark as a form of regulation and feminist self-knowledge.

LUNACEPTION: A FEMININE ODYSSEY INTO FERTILITY AND CONTRACEPTION by LOUIS LACEY

First published in the mid-1970s, it’s out of print but still circulating via used-book sellers. It’s described as:

“A revolutionary frame of reference for looking at your own body; a biologically gratifying way to come into a personal balance with the universe.”

The hard science on strict “moon syncing” is mixed, and cycles are influenced by many factors: stress, hormones, nutrition, trauma, age. But what we do know is very clear:

Light at night changes how we secrete melatonin

Melatonin timing influences sleep, cortisol rhythms, and reproductive hormones

Over time, disrupted light–dark cycles can distort mood, metabolism, and menstrual regularity

So whether or not you bleed on a Full Moon, your endocrine system is listening to light all the time.

DESCARTES, THE PINEAL GLAND, & the FIRST “LIGHT MAP”

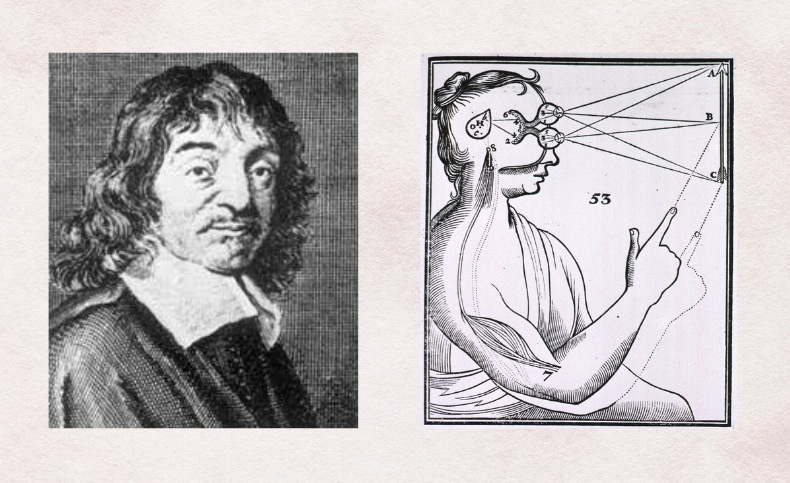

In the 1600s, the philosopher René Descartes drew one of the first diagrams of how light enters the eye and travels into the brain. In his sketch, rays of light pass through the eye, travel along the optic nerves, and converge at a tiny structure he believed to be the meeting point of body and soul: the pineal gland, which he called the “seat of the soul.”

Pictured: René Descartes and his famous diagram of light stimulating the pineal gland.

Modern anatomy refines this, but his intuition was powerful: that light, vision, inner experience, and a central gland are all speaking to one another.

Today we know that:

light hits the retina

signals travel along a special pathway into the brain’s master clock

that clock signals the pineal gland, which releases melatonin when darkness falls

From there, melatonin helps set the timing for sleep, cortisol, thyroid function, ovarian hormones, and more. In other words: Descartes’ hunch that light, perception, and a tiny midline gland were intimately connected turns out to be deeply true.

MELATONIN: EXPLAINED

Melatonin is the body’s hormone of timing.

It’s made in the pineal gland when the eyes report, “Night has arrived.” I don’t think of it as a sedative so much as a signal—a whisper to the endocrine system that it’s safe to cool the mind, soften the edges, and move into repair.

Have you ever taken melatonin and felt really groggy in the morning, heavy in your mood, or strangely “off” the next day?

That’s usually a sign that the dose or timing is not working for your circadian rhythm. It doesn’t necessarily mean melatonin “doesn’t work for you”—it may mean your system needs much less (often 0.5–1 mg, sometimes even 0.3 mg) and/or an earlier time in the evening, not a big hit right before bed.

When I talk about melatonin with patients, I tend to see it as a tool:

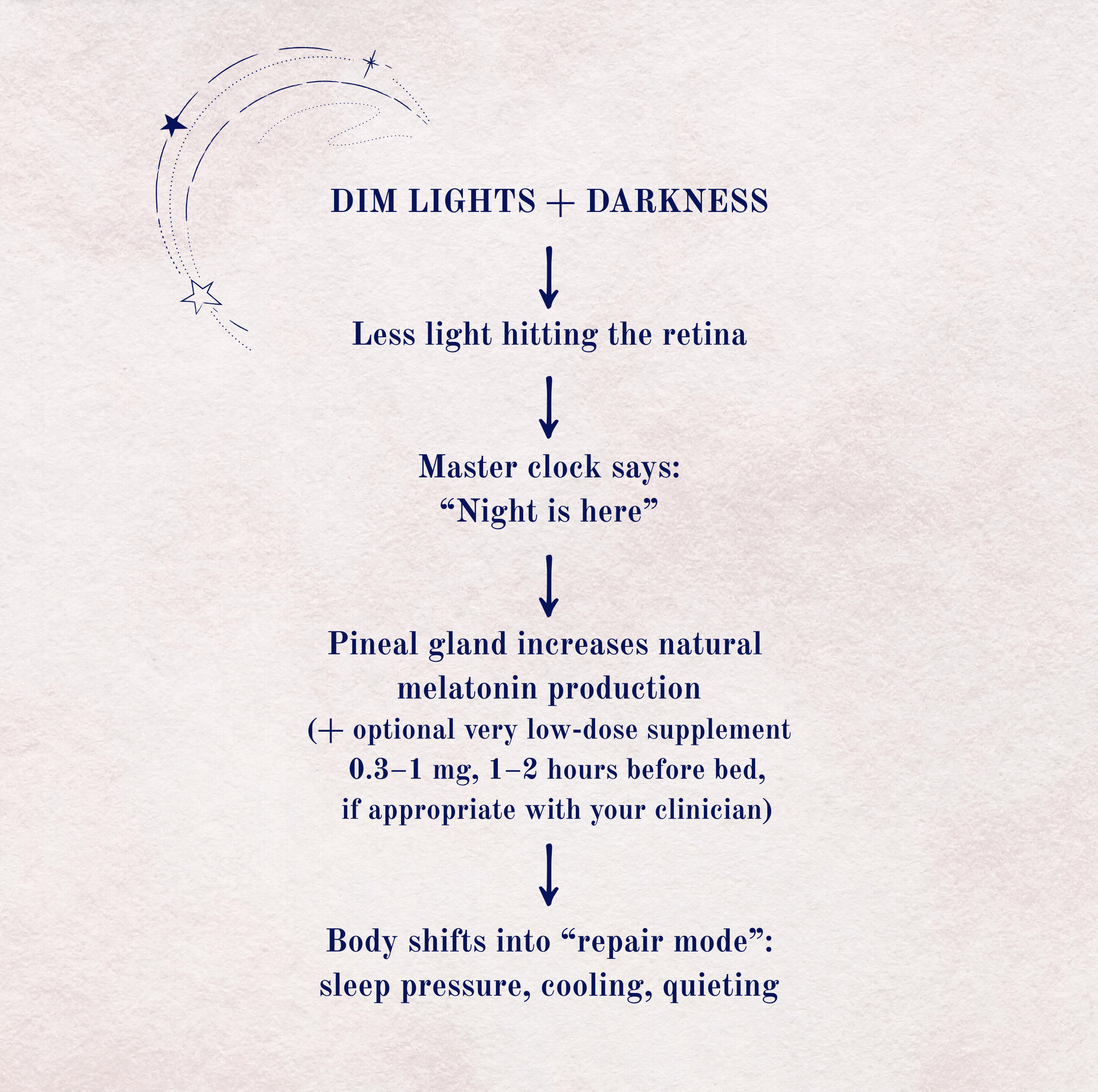

First, we work on light hygiene—dimmer evenings, fewer screens, more morning light

Then, if it feels appropriate, we explore veryj low doses instead of the mega-doses lining store shelves

We use it as a short-term ally to help retrain timing, rather than a forever fix

Melatonin is a hormone made in the pineal gland when the eyes report, “Night has arrived.” It doesn’t force sleep the way a sedative does; it acts more like a timekeeper—a signal that it’s safe for the body to shift from doing to repairing.

When melatonin is released in a clear, consistent rhythm, it helps:

Anchor the circadian clock (our 24-hour body time)

Coordinate sleep onset and depth

Modulate the dance between cortisol, thyroid, and reproductive hormones

Support more coherent menstrual and perimenopausal cycles over tim

When evening light is chaotic—bright screens, overhead LEDs, constant stimulation—the message to the pineal gland gets scrambled. Melatonin may be delayed, blunted, or released at the wrong times, and the body’s internal clocks start to drift. That drift is often felt as:

Irregular or more symptomatic cycles

“Tired but wired” nights

Mood swings around the luteal phase or perimenopause

So when I talk about melatonin, I’m really talking about timing: helping the body remember when night is, so it can remember how to cycle.

Lunaception, darkness rituals, screen boundaries, and—when appropriate, thoughtfully dosed melatonin—are all different ways of sending the same message.

Whether you choose a few nights of true darkness, a tiny dose of melatonin, or simply notice how the light finds you, these are all quiet ways of telling your body: “I see you. Night has arrived. You are safe to rest, repair, and cycle again.”

May the coming dark months feel less like something to power through and more like a gentle return home to yourself.

On your side,

DJV